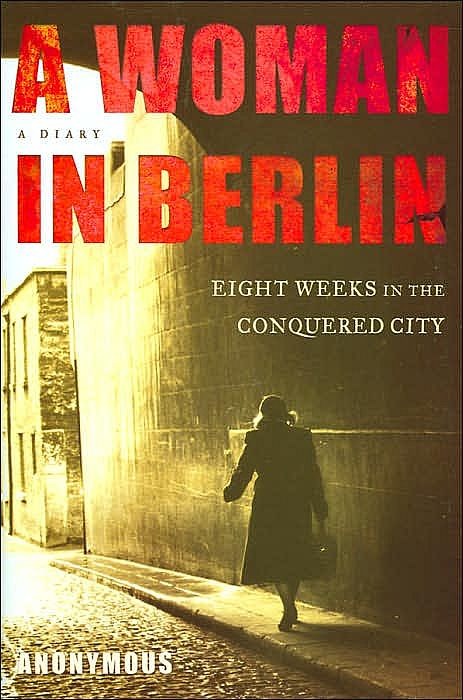

An astonishing find-the landmark journal of a woman living though the Russian occupation of Berlin-which has already earned comparisons to diaries by Etty Hillesum and Victor Klemperer

For six weeks in 1945, as Berlin fell to the Russian army, a young woman, alone in the city, kept a daily record of her and her neighbors' experiences, determined to describe the common lot of millions.

Purged of all self-pity but with laser-sharp observation and bracing humor, the anonymous author conjures up a ravaged apartment building and its little group of residents struggling to get by in the rubble without food, heat, or water. Clear-eyed and unsentimental, she depicts her fellow Berliners in all their humanity as well as their cravenness, corrupted first by hunger and then by the Russians. And with shocking and vivid detail, she tells of the shameful indignities to which women in a conquered city are always subject: the mass rape suffered by all, regardless of age or infirmity. Through this ordeal, she maintains her resilience, decency, and fierce will to come through her city's trial, until normalcy and safety return.

At once an essential record and a work of great literature, A Woman in Berlin not only reveals a true heroine, sure to join other enduring figures of the twentieth century, but also gives voice to the rarely heard victims of war: the women.

The New York Times - Joseph Kanon

The book is graphic and unflinching, with the immediacy of all great diaries (we are always in the present), but what makes it so remarkable is its determination to see beyond the acts themselves. The rapists are not faceless; they have personalities, names (Petka, with the lumberjack hands). They have the contradictions of real people. They are brutal, naïve, even hungry for some kind of connection.

EXCERPT

Friday, 11 pm, by the light of an oil lamp, my notebook on my knees. Around 10 pm there was a series of bombs. The siren started right in screaming. Apparently it has to be worked by hand now. No light. Running downstairs in the dark, we slip and stumble. Finally we're in our cellar, behind an iron door that weighs a hundred pounds. The official term is air-raid shelter. We call it cave, underworld, catacomb of fear.

It's the usual cellar people on the usual cellar chairs, which range from kitchen stools to brocaded armchairs. First is the baker's wife, two plump red cheeks peeking over a lambskin collar. Frau Lehmann whose husband is missing in the east, a pillow-like woman with her sleeping infant on her arm and four-year-old Lutz on her lap, his shoelaces dangling. The young man in gray trousers and horn-rimmed glasses who on closer inspection turns out to be a young woman. Three elderly sisters, dressmakers, huddled together like a big black pudding. The bookselling husband and wife who lived in Paris and often speak French to each other in low voices . . . Then the caretaker's family, consisting of mother, two daughters, and a fatherless grandson. The landlord's housekeeper, who is carrying an aging fox terrier in defiance of all air-raid regulations. And then there's me-a pale-faced blonde always dressed in the same winter coat, which by chance I managed to save, who was employed in a publishing house until it closed last week and sent the employees on leave "until further notice."

It's the usual cellar people on the usual cellar chairs, which range from kitchen stools to brocaded armchairs. First is the baker's wife, two plump red cheeks peeking over a lambskin collar. Frau Lehmann whose husband is missing in the east, a pillow-like woman with her sleeping infant on her arm and four-year-old Lutz on her lap, his shoelaces dangling. The young man in gray trousers and horn-rimmed glasses who on closer inspection turns out to be a young woman. Three elderly sisters, dressmakers, huddled together like a big black pudding. The bookselling husband and wife who lived in Paris and often speak French to each other in low voices . . . Then the caretaker's family, consisting of mother, two daughters, and a fatherless grandson. The landlord's housekeeper, who is carrying an aging fox terrier in defiance of all air-raid regulations. And then there's me-a pale-faced blonde always dressed in the same winter coat, which by chance I managed to save, who was employed in a publishing house until it closed last week and sent the employees on leave "until further notice."

No comments:

Post a Comment