|

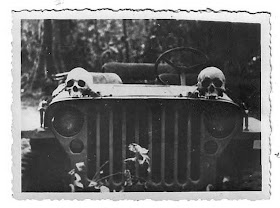

| Japanese Heads used as Jeep Headlights |

During World War II, United States military personnel mutilated dead Japanese service personnel in the Pacific theater of operations. The mutilation of Japanese service personnel included the taking of body parts as “war souvenirs” and “war trophies”. Teeth and skulls were the most commonly taken "trophies", although other body parts were also collected.

The phenomenon of "trophy-taking" was widespread enough that discussion of it featured prominently in magazines and newspapers, and Franklin Roosevelt himself was reportedly given a gift of a letter-opener made of a man's arm (Roosevelt rejected the gift and called for its proper burial). The behavior was officially prohibited by the U.S. military, which issued additional guidance as early as 1942 condemning it specifically. Nonetheless, the behavior continued throughout the war in the Pacific Theater, and has resulted in continued discoveries of "trophy skulls" of Japanese combatants in American possession, as well as American and Japanese efforts to repatriate the remains of the Japanese dead.

The earliest account of U.S. troops wearing ears from Japanese corpses he recounts took according to one Marine place on the second day of the Guadalcanal Campaign in August 1942 and occurred after photos of the mutilated bodies of Marines on Wake Island were found in Japanese engineers' personal effects. The account of the same marine also states that Japanese troops booby trapped some of their own dead as well as some dead marines, and also mutilated corpses; the effect on marines being "We began to get down to their level". According to Bradley A. Thayer, referring to Bergerud and interviews conducted by Bergerud, the behaviors of American and Australian soldiers were affected by "intense fear, coupled with a powerful lust for revenge".

Weingartner writes however that U.S. Marines were intent on taking gold teeth and making keepsakes of Japanese ears already while en-route to Guadacanal.

"Japanese skulls were much-envied trophies among U.S. Marines in the Pacific theater during World War II. The practice of collecting them apparently began after the bloody conflict on Guadalcanal, when the troops set up the skulls as ornaments or totems atop poles as a type of warning. The Marines boiled the skulls and then used lye to remove any residual flesh so they would be suitable as souvenirs. U.S. sailors cleaned their trophy skulls by putting them in nets and dragging them behind their vessels. Winfield Townley Scott wrote a wartime poem, 'The U.S. Sailor with the Japanese Skull" that detailed the entire technique of preserving the headskull as a souvenir. Referring to this practice, Edward L. Jones, a U.S. war correspondent in the Pacific wrote in the February 1946 Atlantic Magazine, "We boiled the flesh off enemy skulls to make table ornaments for sweethearts, or carved their bones into letter-openers." On occasion, these "Japanese trophy skulls" have confused police when they have turned up during murder investigations. It has been reported that when the remains of Japanese soldiers were repatriated from the Mariana Islands in 1984, sixty percent were missing their skulls."

The collection of Japanese body parts began quite early in the war, prompting a September 1942 order for disciplinary action against such souvenir taking.

Harrison concludes that, since this was the first real opportunity to take such items (The Battle of Guadalcanal), "clearly, the collection of body parts on a scale large enough to concern the military authorities had started as soon as the first living or dead Japanese bodies were encountered."

When Japanese remains were repatriated from the Mariana Islands after the war, roughly 60 percent were missing their skulls.

|

| Japanese soldier's decapitated head hung on a tree branch in Burma, probably by American soldiers. 1945. Source of Photo; US National Archives. |

Eugene Sledge relates a few instances of fellow Marines extracting gold teeth from the Japanese, including one from an enemy soldier who was still alive.

But the Japanese wasn't dead. He had been wounded severely in the back and couldn't move his arms; otherwise he would have resisted to his last breath. The Japanese's mouth glowed with huge gold-crowned teeth, and his captor wanted them. He put the point of his kabar on the base of a tooth and hit the handle with the palm of his hand. Because the Japanese was kicking his feet and thrashing about, the knife point glanced off the tooth and sank deeply into the victim's mouth. The Marine cursed him and with a slash cut his cheeks open to each ear. He put his foot on the sufferer's lower jaw and tried again. Blood poured out of the soldier's mouth. He made a gurgling noise and thrashed wildly. I shouted, “Put the man out of his misery.” All I got for an answer was a cussing out. Another Marine ran up, put a bullet in the enemy soldier's brain, and ended his agony. The scavenger grumbled and continued extracting his prizes undisturbed.

In October 1943, the U.S. High Command expressed alarm over recent newspaper articles, for example one where a soldier made a string of beads using Japanese teeth, and another about a soldier with pictures showing the steps in preparing a skull, involving cooking and scraping of the Japanese heads.

Skull stewing Charles Lindbergh refers in his diary to a conversation he had with a marine officer, who claimed that he had seen many Japanese corpses with an ear or nose cut off. In the case of the skulls however, most were not collected from freshly killed Japanese; most came from already partially or fully skeletonised Japanese bodies.

| ||

| Front line warning sign using a Japanese soldier's skull on Peleliu Source: - National Park Service - National Archives #98501 |

These practises were in addition also in violation of the unwritten customary rules of land warfare and could lead to the death penalty. The U.S. Navy JAG mirrored that opinion one week later, and also added that "the atrocious conduct of which some US personnel were guilty could lead to retaliation by the Japanese which would be justified under international law".

RELATED

Sources:

James J. Weingartner "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941–1945" Pacific Historical Review (1992)

Simon Harrison “Skull Trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S) 12, 817–836 (2006)

Kenneth V. Iserson, M.D., Death to Dust: What happens to Dead Bodies?, Galen Press, Ltd. Tucson, AZ. 1994.

Bradley A. Thayer, "Darwin and international relations"

Article Source: http://www.canadaatwar.ca/forums/showthread.php?t=2398

No comments:

Post a Comment