In the early 1960s, Czechoslovakia, then officially known as the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR), underwent an economic downturn. The Soviet model of industrialization applied poorly to Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia was already quite industrialized before World War II and the Soviet model mainly took into account less developed economies. Novotný's attempt at restructuring the economy, the 1965 New Economic Model, spurred increased demand for political reform as well

------

In the early 1960s the country suffered an economic recession. Antonin Novotny, the president of Czechoslovakia, was forced to make liberal concessions and in 1965 he introduced a programme of decentralization. The main feature of the new system was that individual companies would have more freedom to decide on prices and wages.

These reforms were slow to make an impact on the Czech economy and in September 1967, Dubcek presented a long list of grievances against the government. The following month there were large demonstrations against Novotny.

In January 1968 the Czechoslovak Party Central Committee passed a vote of no confidence in Antonin Novotny and he was replaced by Dubcek as party secretary. Gustav Husak, a Dubcek supporter, became his deputy. Soon afterwards Dubcek made a speech where he stated: "We shall have to remove everything that strangles artistic and scientific creativeness."

During what became known as the Prague Spring, Dubcek announced a series of reforms. This included the abolition of censorship and the right of citizens to criticize the government. Newspapers began publishing revelations about corruption in high places. This included stories about Novotny and his son. On 22nd March 1968, Novotny resigned as president of Czechoslovakia. He was now replaced by a Dubcek supporter, Ludvik Svoboda.

In April 1968 the Communist Party Central Committee published a detailed attack on Novotny's government. This included its poor record concerning housing, living standards and transport. It also announced a complete change in the role of the party member. It criticized the traditional view of members being forced to provide unconditional obedience to party policy. Instead it declared that each member "has not only the right, but the duty to act according to his conscience."

The new reform programme included the creation of works councils in industry, increased rights for trade unions to bargain on behalf of its members and the right of farmers to form independent co-operatives.

Source: Spartacus

Soviet troops began entering Czechoslovakia late on August 20th and early August 21st in a carefully orchestrated invasion designed to crush the period of political and economic reforms known as the Prague Spring, reforms led by the country's new First Secretary of the Communist party Alexander Dubcek. A movement viewed by Leonid Brezhnev and other Soviet hard-liners in Moscow as a serious threat to the Soviet Union's hold on the Socialist satellite states, they decided to act. In the first hours on the 21st Soviet planes began to land unexpectedly at Prague's Ruzyne airport, and shortly Soviet tanks would roll through Prague's narrow streets. Within hours foreign troops would take up strategic positions throughout the city, including surrounding the building of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, taking hold of Wenceslas Square, and eventually taking over Czechoslovak radio and television. The occupation of '68 had begun.

Source

"I was sleeping soundly when a friend from New York called me and said 'Have you evacuated the family?' I answered 'Why should I?' and he said 'Prague has been invaded, the airport has been seized, and the Castle is under Russian control..."

American editor Alan Levy was a foreign correspondent in Czechoslovakia in 1968. On August 21st he witnessed some of the first tanks as they steered their way in to the Czech capital.

"I got dressed and went out with my sixteen year-old niece who was staying with us and we didn't see any Russians for a while until in Pohorelec dozen tanks rolled out down the ramp out of Strahov. They were lost. They couldn't find the Castle. They had a tourist map and nothing else. And, they started pointing guns at the crowd and nobody would tell them. When your life almost ends, when a man with his finger on the trigger points it at you is getting ready to shoot - in my case he was ready to shoot at a taxi he thought might be alerting the troops - you're on borrowed time."

It was the most bitter of realisations. For believers in socialism - like Dubcek and other party reformers - it was a betrayal, by partners within the Warsaw pact. Poland, Hungary, East Germany, Bulgaria, the Soviet Union. On the other hand, for long-time opponents to the regime it was final damning proof that at its core Moscow had always been tyrannical - willing to stop at nothing to exercise its will. The Prague Spring, the series of reforms and cultural freedom - including the lifting of censorship, the creation of dialogue, the addressing of past wrongs and new openness in published books and the press - that had been so thoroughly embraced over the last eight months, would prove a short-lived experiment. Socialism with a human face would be stamped out by the presence of more than 200, 000 foreign soldiers, who would triple in number by the end of the week.

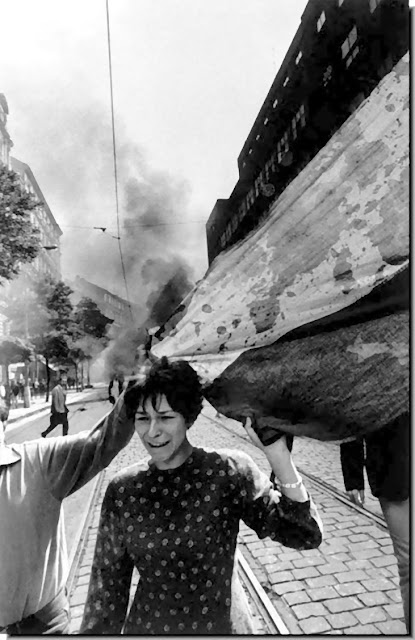

Meanwhile, on the morning of the 21st, shooting had begun at the Czechoslovak Radio building on Vinohradska Street. After the station broadcast a statement by the Central Committee of the Czechoslovak Communist Party condemning the invasion, Prague citizens gathered at the building to defend the strategic site. Soon, however, broadcasts would be cut off. The last few sentences on the air told Czechs and the rest of the world they had only ever wanted humanistic socialism, adding truth would prevail. Broadcasters were then cut off in mid-sentence as the anthem played, while outside in front of the radio building, several Prague citizens already lay dead.

Kamila Mouckova, a well-known news anchor in Czechoslovakia at that time, knew she had to make her way to Czechoslovak TV, in the city centre, to provide whatever service she could.

"I was very upset. In the morning I drove to a nearby gas-station, and it was there, on the steps of building of the Central Committee of the Communist Party that I saw the first body. It was a young man. To this day I can not describe the feeling in me that this evoked."

At the TV station they broadcast reports throughout the morning of the 21st, while there was still time. Mrs Mouckova says she tried to appeal for calm. After all, could anybody really believe such a sordid state of events would continue? She, for one, did not.

"I tried to get people to pull back, to stay at home, not to go out onto the streets. That it was all just some kind of mistake that events would turn out better in the end."

But, as more and more reports of spontaneous demonstrations and clashes and killing of Czechs emerged, an ever-growing feeling of rage and disbelief began to dominate.

"You know what the primary feeling was? It was terrible - there's no nice way of saying it - I was terribly, terribly angry. I was so furious I was practically foaming at the mouth. I couldn't believe what they had done - the audacity and nerve! The invasion, forcing us out at gunpoint then taking aim at us when they finally uprooted us from our illegal radio broadcast point six days later. By then, it had occurred to each one of us we really might end up lined up against a wall."

The future of their country was not something the Czechs gave up lightly, although there was little hope. They protested in the thousands for days. They clashed, and they pleaded, they hung up placards, and slogans, and wrote graffiti on the walls, crying a common appeal for justice. In their protest, says political scientist Zdenek Zboril, there was simple genius - emotional to observe even thirty-five years after the event.

"I am happy that I could see the spontaneous resistance of the people on the streets, on the posters on the walls. It was unbelievable. It was poetry, jokes, irony - it was an answer to the brutal Soviet invasion. One slogan was typical for this attitude - originally the slogan read 'With the Soviet Union for All Eternity'. But, in that time Czechs came up with the slogan 'With the Soviet Union for Eternity - but not a single day more!"

VIDEO

VIDEO

TV anchor Kamila Mouckova:

"Every nation has its history, and everybody should know the history of their own nation. The days of August 1968 are of course key. This is not about cramming facts in school - this is about the challenge for all of us to learn from the event so that it will never again be repeated."

1968 - A year that began with hope and promise for Czechoslovakia and ended in tragedy no one could have foreseen. It changed the direction of a country, and the lives of millions. The last Russian troops finally left Czech soil in 1991.

Source

One of the immediate causes of the Soviet invasion, aside from mounting fears that Dubcek could not control popular pressure for change, was the plan to convene a Fourteenth Party Congress in September 1968, whose delegates would elect a solidly pro-reform Central Committee. The invasion changed the schedule, and the Congress was held on August 22nd--over a thousand delegates disguised as workers made it past Soviet troops to convene at a factory in Vysocany outside Prague. It issued proclamations condemning the invasion, supporting the reform process, and threatening a one-hour general strike (document 2A). The strike took place as planned, but power was already shifting out of the reformers' hands.

Hastily worded pamphlets and flyers, often with typos, often mimeographed on cheap paper, spread information about the occupation, calling on Czechoslovaks to resist peacefully and reaffirming popular loyalty to Dubcek and the other reform leaders, who had been interned in the early hours of the invasion and shipped off to Moscow for "negotiations" about the country's future. Newspapers and magazines continued to publish, often with the words "Legal" or "Free" added to the masthead to indicate that they were not in the hands of the occupiers . Radio continued to broadcast from secret transmitters even after the central radio building in Prague had been battered into submission . Flyers printed in Russian were designed to explain the situation to Soviet soldiers, many of whom had little idea of where they were or what they were doing there . Graffiti in Russian was also common

WHAT HAPPENED NEXT?

At the same time, a careful reading of the documents reveals some curiosities. Proclamations and declarations from Communist party organs opposing the invasion employed all the standard jargon of Communist ideology, appealing in characteristically clunky syntax to the international workers' movement and the country's workers - a linguistic affinity underlining the fact that the reforms had, after all, been carried out in a socialist framework. Above all, these materials illustrate a central paradox of the invasion: both occupiers and resisters consistently called for calm, peace, and quiet, echoing Dubcek's and Svoboda's appeals to maintain order. The call for "calm and level-headedness" (klid a rozvaha) was repeated over and over, and the demand for a "normalization" of the tense situation would become a mantra of both sides. Many Czechoslovaks, facing a far superior military force, did not want to provide the occupying forces with a pretext for violent crackdowns; much of the popular resistance to the invasion would be passive and dignified . The invaders themselves wanted to forestall violent opposition . In the aftermath of August 21, both Czechoslovakia's legitimate leaders and the occupiers aimed at the same goal, however differently they understood it: securing the normal functioning of daily life in the country.

The country persisted in this strange state of tentative resistance for months. The reform leaders who had been interned and brought to Moscow for negotiations were more or less forced to sign the so-called Moscow Protocol, which declared the 14th Congress invalid, re-instituted controls over the media, and rolled back the reforms in other ways - all topped off with a promise by the Czechoslovak and Soviet governments to "intensify . . . their fraternal friendship for time everlasting." The only person not to sign the Protocol, Chairman of the National Front Frantisek Kriegel, was subsequently stripped of all his functions and finally expelled from the party in 1969 . Other reform leaders, including Dubcek, were allowed to maintain their functions and even some power, but they tended to discourage public displays of discontent for fear of provoking their Soviet overseers. At the end of March 1969, the Czechoslovak ice hockey team defeated the Soviets, a victory that sparked mass demonstrations throughout the country and finally provided the pretext for a full-scale crackdown . Dubcek was ousted as Party Secretary by the opportunistic, brutally colorless functionary Gustav Husak, who presided over an ever-strengthening purge of the party and society. Protests on August 21, 1969 were brutally suppressed and turned out to be the last mass demonstrations against the invasion, as the country settled down into the gray years of bureaucratic oppression known as "normalization."

2 Comments:

Thanks to whoever wrote this. One of my favorite books is The Unbearable Lightness of Being and this sight really helped me visualise what was happening then.

There's one thing that was forgotten:Romania was THE ONLY SOCIALIST country who didn't participate to Czechoslovakia's invasion!

Romania refused to be a part in such a disgrace!

Post a Comment