BATTLE OF GREECE

In Brief

Initially the war against Germany and Italy went very well for Greece. The nation rallied behind Metaxas, and men of all political persuasions joined the military. Under the leadership of General Georgios Tsolakoglou, the Greek army in Epirus drove the Italians out of Greece and through most of Albania by early December. For many Greeks, this campaign was an opportunity to liberate their countrymen across the Albanian border in "Northern Epirus." The campaign stalled in cold weather, then it lost its leader, Metaxas, who died in January 1941. The British, who at this time had no other active ally in the region, provided air and ground support. But poor coordination between the allied forces made Greece vulnerable to a massive German attack in the spring of 1941, which was intended to secure the Nazi southern flank in preparation for the invasion of Russia. Under the German blitzkrieg, the Greek and British forces quickly fell. Most of the British force escaped, but Tsolakoglou, trapped between the Italian and the German armies, was forced to capitulate. Athens fell shortly afterward as the second element of the German invasion force rushed southward. King George II, his government, and the remnants of the Greek army fled to Crete. Crete fell the next month, however, and George established a government-in-exile in Egypt.

was a World War II battle that occurred on the Greek mainland and in southern Albania. The battle was fought between the Allied (Greece and the British Commonwealth) and Axis (Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Bulgaria) forces. With the Battle of Crete and several naval actions, the Battle of Greece is considered part of the wider Aegean component of the Balkans Campaign of World War II.

The Battle of Greece is generally regarded as a continuation of the Greco-Italian War, which began when Italian troops invaded Greece on 28 October 1940. Within weeks the Italians were driven out of Greece and Greek forces pushed on to occupy much of southern Albania. In March 1941, a major Italian counterattack failed, and Germany was forced to come to the aid of its ally. Operation Marita began on 6 April 1941, with German troops invading Greece through Bulgaria in an effort to secure its southern flank. The combined Greek and British Commonwealth forces fought back with great tenacity, but were vastly outnumbered and out-gunned, and finally collapsed. Athens fell on 27 April. However, the British managed to evacuate about 50,000 troops. The Greek campaign ended in a quick and complete German victory with the fall of Kalamata in the Peloponnese; it was over within twenty-four days. Nevertheless, both German and Allied officials have expressed their admiration for the strong resistance of the Greek soldiers.

Others believed British intervention in Greece as a hopeless undertaking, a "political and sentimental decision" or even a "definite strategic blunder." It has also been suggested the British strategy was to create a barrier in Greece, to protect Turkey, the only (neutral) country standing between an Axis block in the Balkans and the oil-rich Middle East.

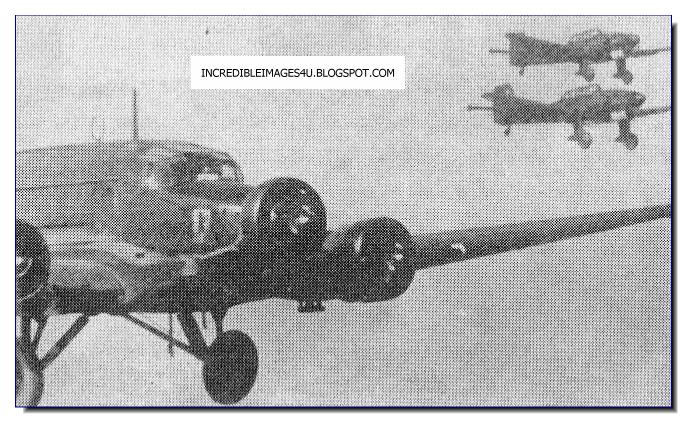

A Junker 52 transport plane escorted by Junker 87 dive bombers in Crete

BATTLE OF CRETE

The Battle of Crete (German: Luftlandeschlacht um Kreta) was a battle during World War II on the Greek island of Crete. It began on the morning of 20 May 1941, when Nazi Germany launched an airborne invasion of Crete under the code-name Unternehmen Merkur ("Operation Mercury"). Greek and Allied forces, along with Cretan civilians, defended the island.

After one day of fighting, the Germans had suffered appalling casualties and none of their objectives had been achieved. The next day, through miscommunication and the failure of Allied commanders to grasp the situation, Maleme airfield in western Crete fell to the Germans, enabling them to fly in reinforcements and overwhelm the defenders. The battle lasted about 10 days.

The Battle of Crete was unprecedented in three respects: it was the first mainly airborne invasion; the first time the Allies made significant use of intelligence from the deciphered German Enigma code; and the first time invading German troops encountered mass resistance from a civilian population. In light of the heavy casualties suffered by the paratroopers, Adolf Hitler forbade further large scale airborne operations. However, the Allies were impressed by the potential of paratroopers and started to build their own airborne divisions. This was the first battle where the Fallschirmjäger ("parachute rangers") were used on a massive scale.

German soldiers rest in a olive orchard in Crete

Winston Churchill believed it was vital for the UK to take every measure possible to support Greece. On January 8, 1941, he stated that "there was no other course open to us but to make certain that we had spared no effort to help the Greeks who had shown themselves so worthy

Germans paratroopers land in Crete

Allied newspapers dubbed the Greek army's fate as a modern day Greek tragedy. Historian and former war-correspondent, Christopher Buckley, when describing the fate of the Greek army, stated that "one experience[d] a genuine Aristotelian catharsis, an awe-inspiring sense of the futility of all human effort and all human courage."

The Germans drove straight to the Acropolis and raised the Nazi flag. According to the most popular account of the events, the Evzone soldier on guard duty, Konstantinos Koukidis, took down the Greek flag, refusing to hand it to the invaders wrapped himself in it, and jumped off the Acropolis. Whether the story was true or not, many Greeks believed it and viewed the soldier as a martyr.

Troops of the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler negotiate difficult terrain in Greece, 1941

Little news from Greece, but 13,000 men got away to Crete on Friday night, and so there are hopes of a decent percentage of evacuation. It is a terrible anxiety [...] War Cabinet. Winston says "We will lose only 5,000 in Greece." We will in fact lose at least 15,000. W. is a great man, but he is more addicted to wishful thinking every day.

Robert Menzies, Excerpts from his personal diary, April 27 and 28, 1941

German paratroopers land in Crete and immediately engage in battle with numerically superior allied forces

WHY WAS THE GERMAN VICTORY IN GREECE SO COMPLETE?

- Germany's superiority in ground forces and equipment;

German supremacy in the air combined with the inability of the Greeks to provide the RAF with more airfields;

Inadequacy of the British expeditionary force, since the Imperial force available was small;

Poor condition of the Greek Army and its shortage of modern equipment;

Inadequate port, road and railway facilities;

Absence of a unified command and lack of cooperation between the British, Greek, and Yugoslav forces;

Turkey's strict neutrality;and

The early collapse of Yugoslav resistance.

Two German paratroopers in Crete

THE BRAVE GREEKS

In a speech made at the Reichstag in 1941, Hitler expressed his admiration for the Greek resistance, saying of the campaign: "Historical justice obliges me to state that of the enemies who took up positions against us, the Greek soldier particularly fought with the highest courage. He capitulated only when further resistance had become impossible and useless." The Führer also ordered the release and repatriation of all Greek prisoners of war, as soon as they had been disarmed, "because of their gallant bearing." According to Hitler's Chief of Staff, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, the Führer "wanted to give the Greeks an honorable settlement in recognition of their brave struggle, and of their blamelessness for this war: after all the Italians had started it."

Inspired by the Greek resistance during the Italian and German invasions, Churchill said, "Hence we will not say that Greeks fight like heroes, but that heroes fight like Greeks".

In response to a letter from George VI dated 3 December 1940, American President Franklin D. Roosevelt stated that "all free peoples are deeply impressed by the courage and steadfastness of the Greek nation", and in a letter to the Greek ambassador dated 29 October 1942, he wrote that "Greece has set the example which every one of us must follow until the despoilers of freedom everywhere have been brought to their just doom."

The then Colonel Hermann-Bernhard "Gerhard" Ramcke with his paratroopers

British soldiers surrender in Crete

A rather grim looking Major General Freyberg, allied commander in Crete

British soldiers await the Germans in Greece

A truckful of Greek POW

Meeting of the German generals to discuss the surrender of the Greek army. From left to right - Colonel-General Josef Dietrich Zep (Generaloberst Dietrich, Joseph (Sepp): SS-Oberstgruppenführer, Leibstandarte), Lieutenant-General Hans von Greyfenberg (Generalleutnant Greiffenberg, Hans von) and Field Marshal Wilhelm List (Generalfeldmarschall List, Wilhelm )

A 33 mm gun mounted on the chassis of a panzer 1 tank. 5th Panzer Division. April 1941. Greece

A German 3.7 cm anti-aircraft gun

VIDEO: THE IMPORTANCE OF GREEKS DURING WW2

"Jews unwelcome"

German mountain troops prior to going to Crete

Wonder who the glum looking officer is. Greek or British?

British POW at Nauplion, Greece. May 1941

German soldiers sunbathing in Greece

Ah! The joy of bathing!

German soldiers of the 2nd Armored Division question a captured New Zealand soldier in Greece

June 11, 1941. Battle hardened German paratroopers in Crete

1 Comment:

War is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

Your article is very well done, a good read.

Post a Comment